This topic was inspired by some of my pairing sessions with my colleague Tobias Bieniek and the concepts laid out in this post have become invaluable to me while working with open source development. If you haven't already checked out Tobias' blog on Open Source maintenance I would highly recommend checking it out after reading this post 🎉

anchorGit complexities

Git can sometimes be complex to get your head around. Most of us learn Git up to a point where we're happy to use it day-to-day and then stick to the few commands that we are comfortable with without trying anything too fancy. Most of the time this works out, but then every so often we do something wrong or someone asks us to rebase or "squash" something and we either panic and/or mess up our git repo 😫 This is such a common feeling that sites like Oh shit, git! have cropped up to help us get out of our messes.

It's my belief that a number of factors have held developers back from becoming super productive with Git, and with a bit of guidance in pairing sessions I can usually help people to unlock their full potential while using Git. This potential I am talking about is not anything so complex as dealing with the reflog, or knowing anything about blobs or the internals of Git, I am just talking about people feeling comfortable understanding branches, rebasing, cherrypicking, and have the ability to clean up a branch before submitting it to a Pull Request (PR).

The most egregious thing that holds back people's understanding of Git is the concept that "if you don't use git on the command line then you're not a real developer" and this idea it needs to die. Sure there are plenty of places in the tech community where we have a gatekeeper problem, but this particular idea of "you're not a real developer if you don't do X" is the most pervasive and destructive. The fact that we funnel so many junior and intermediate developers into using git on the command line, I believe, has significantly hampered their ability to truly master Git.

This is why, whenever I get the chance, I always recommend people to just download Fork. I have always been a visual learner so when I think about Git I very much see the branching model in my head. Even if you don't know exactly what you're looking at when you see the Fork interface, you will pick up the concepts of branching in Git much faster when you see a command's effect on the tree visualisation rather than an abstract set of characters in the command line.

anchorIt's all in the eye of the reviewer

So what is the point of mastering Git and becoming a rebasing wizard with the ability to rewrite history like you are Hermione Granger wielding a time turner‽

The point of this post is not to get everyone rebasing their branches for the sake of feeling cool, but instead I hope that more people learn just enough Git skills to achieve one simple goal: make your pull requests more focused and understandable to improve their chance of getting merged quickly (or even getting merged at all).

Making sure your pull requests have a good Git history can really streamline the review process for your colleagues or maintainers of Open Source projects, and has the added benefit of keeping the Git history clean in the long run. This will help your colleagues, or even your future self, understand the thought process behind your PR if you ever need to go back and do some code archaeology to figure out why something was added or changed in the codebase.

Open source projects tend to receive a large number of PRs out of the blue, some of them are great but sometimes you get the dreaded "rewrite all your code" PR. These are often very hard to ever get merged (if you would even want to merge them) because they end up touching too much stuff in the same PR and can make it next to impossible to review properly.

I like to say to people interested in getting involved in OSS "the smaller the PR the more likely it will be to get merged". This doesn't just apply to external contributors. When I'm working on any Open Source project that I manage, I try to take this into account and split any large rewrite or substantial change into a series of smaller iterations.

It is also important to note that when I refer to a "change" I'm not referring to the classic Git reporting of number of lines changed. We are not computers and we don't really care how many bits were flipped in a Pull Request. What we really care about is the number of concepts that changed in a particular PR. I have discussed this a bit with my colleagues and the best example I can come up with is that I don't mind a PR that fixes 1000 instances of a linting rule as long as it's the same conceptual change in all lines that are changed. If you change 10 instances of one rule and 1 instance of another rule, the cognitive load of reviewing that PR becomes too much.

While this post inspired by my work in open source, I have also recently given a Git Workshop for a client where we communicated the exact same concepts: "the smaller the PR the more likely it will be to get merged quickly". And if you or your employer cares about efficiency then this can only be a good thing 😉

anchorSmallest number of commits for the smallest conceptual change

So far I have been writing in terms of abstract ideas. This may be useful to a few people but I think most people would find it a bit difficult to convert what I have said so far into meaningful strategies to improve their Pull Requests in future. Let's look at a concrete example that illustrates the point that I'm trying to make with this blog.

Let's assume you now have a good "small" PR. I am calling this "small" because it might have a lot of lines changed, but it is only one conceptual change as I described in the last section. This PR of yours may be small from a conceptual perspective, but it may have taken you quite a few commits to complete it. Here is an example PR that I know has too many commits: https://github.com/ember-learn/guides-app/pull/19

If you look at the list of commits you will see commit messages that look like:

- Testing Percy integration

- Revert "testing percy integration"

- fixing the Percy ignore rules

This is a great example of something that isn't very helpful for people reviewing, and it also doesn't tell us anything meaningful about the work that was done. This is essentially showing everyone your failed experiments and is one of the examples of things that are so objectively unhelpful that we can even make a rule about it:

Rule 1: Don't waste your reviewer's time by showing them all your failed experiments in your Git history.

Some people might see commits like this and use this as a justification to recommend squashing commits when merging this PR. I happen to disagree with this sentiment because I believe this wipes out all the history of what happened in this PR. Git history is fundamentally useful, as long as it is clean.

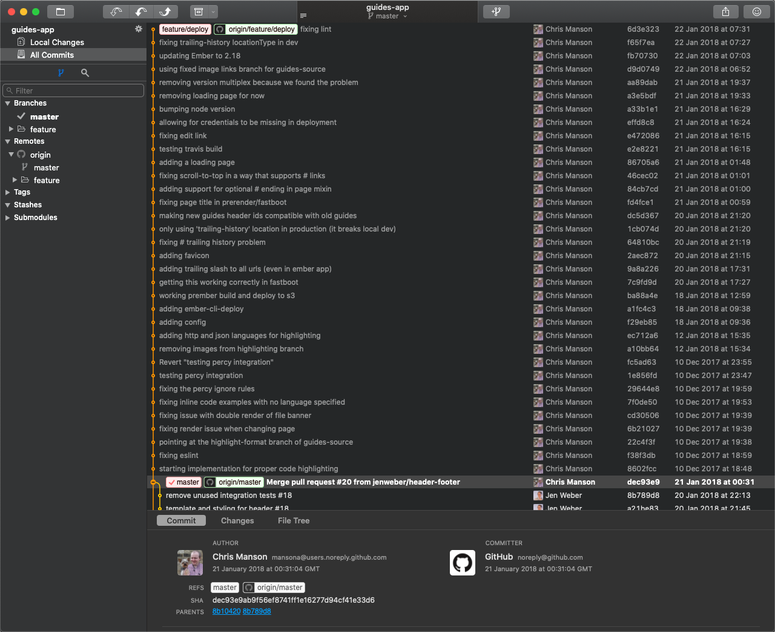

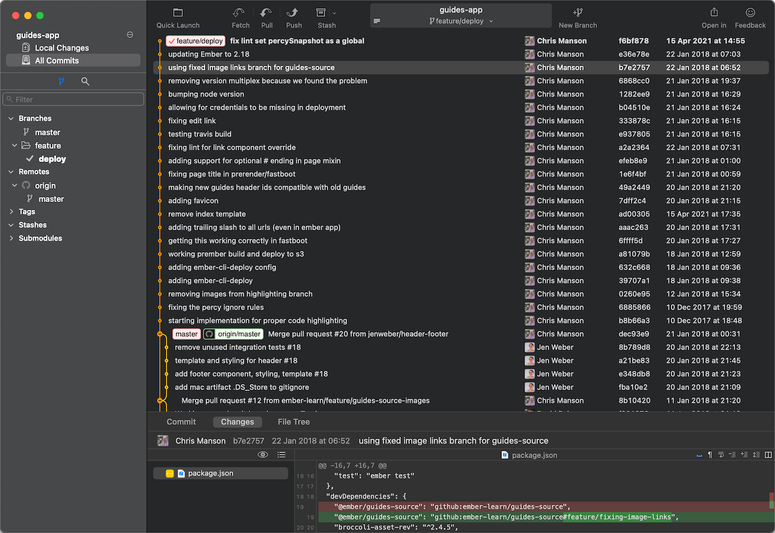

In case anyone doesn't know exactly what I mean by "squashing commits when merging this PR" let me show you the Git history when you do a squash-merge and compare it to a merge-commit. Here is a screenshot of what the branch looks like before you have merged anything:

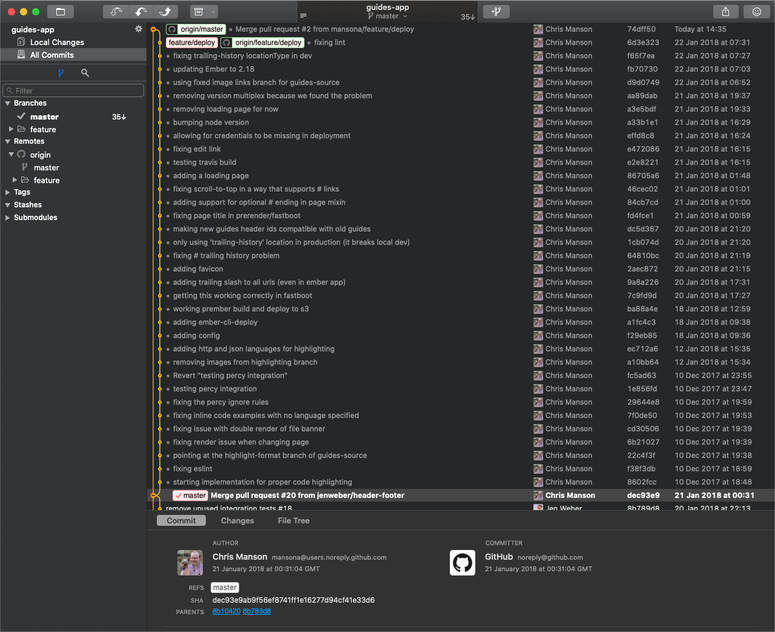

The following photo is what it looks like when you create a merge commit when merging on Github (the default behaviour):

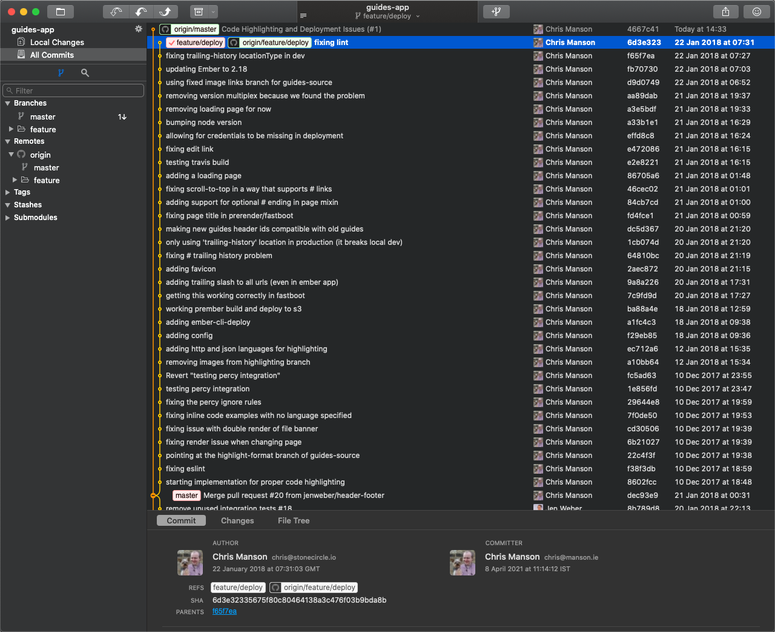

This next photo is the same merge action on Github but this time using the "squash and merge" functionality of Github:

You might think that there isn't much of a difference between these screenshots, and from a "code on disk" perspective you would be right. The same code will be in the master branch at the end of both of these operations, but as you can see the history is very different. You are only able to see the previous commits in this example because they are still on the remote origin/feature/deploy branch and I have a local copy of that branch on my computer. If you delete that remote branch all other contributors to this repo in the future would see a history that looks a little bit more like this:

As I mentioned at the beginning of this post, you should always be thinking about brave explorers that may be digging into the history of your code a year from now trying to figure out what was done and why it was done that way. A single commit that has a diff with +4,762 −1,368 changes will be very hard to understand and will likely slow down anyone who is doing serious code archaeology.

These examples all come from a branch that I created for a now deprecated repository. As it turns out, the branch was so big and the history was so unhelpful that whoever merged that branch chose to squash and merge so the history was lost. I was only able to revive the history for these examples using some extreme git mastery that is far above what a reasonable code archaeologist should be expected to do when trying to figure out what happened, and which also doesn't work if you're trying to do a git-bisect to find the source of an issue.

The answer to this problem is to maintain a Git history closest to the true essence of the work done, creating a number of small PRs that each makes one releasable change to the codebase and keeping the number of commits as low as possible. The question becomes, how can we effectively do that?

anchorRebasing, fixups, and moderate git mastery - a case study

I'm going to spend some time actually fixing the PR that I was using as an example in the previous section. This way you can see a practical example and see a good before-and-after shot to compare the difference. I will also go into some detail about each technique that I will use to actually perform the changes in question.

Some of the techniques that I will be using are rebase, interactive rebase, fixup, cherrypicking, and commit splitting. Reading this list you might feel like this article is targeted at the advanced Git user, but I would say that this is not the case. With a tiny bit of guidance I believe every developer can start making use of these powerful intermediate git tools and improve their workflows.

First things first, if you want to follow along with my examples you will need to install the Git client called Fork. I now use Fork exclusively when I'm trying to do anything that requires you to have an image of the Git history in your mind. This is mainly because it gives you such a great visualisation of the history and you can actively see the effect your changes have. Each of the examples in the previous section are screenshots from Fork.

It is also worth mentioning that using Fork is not something that I consider optional for the techniques that I am about to go through. Sure you can achieve everything that I'm about to show you using only the command line, but I have seen much more experienced developers than I struggle and make catastrophic mistakes while using git on the command line. When people see examples of what I do regularly with git and think I'm some sort of Git wizard, I usually tell them that I'm just playing the game on easy mode using a visual Git tool like Fork. If you take anything away from this article let it be to ignore any gatekeepers in the industry that might tell you "you're not a real developer if you don't use Git on the command line" and just start using Fork for 90% of the operations that you do with Git.

Now it's time to get started. The first thing that I like to do when trying to split a giant PR into multiple smaller PRs is to go through each of the commits and see very roughly what they are doing. This gives you a feeling for what the overall PR is trying to achieve and it should allow you to locate any smaller issues that can be fixed right away. To do this I literally just click through each commit on the branch and browse some of the changes in Fork, starting at the bottom of the branch in Fork because the oldest commit is at the bottom and the newest is at the top.

Looking through the commits I have already seen a whole bunch of simple issues that could be fixed. The most obvious and easiest to fix is the pair of commits testing percy integration and Revert "testing percy integration". This is a perfect example of the thing I said earlier in this post where you should not show the reviewer your failed experiments. If our branch didn't have either of these commits the outcome would be exactly the same, so let's remove them!

Note: Instead of trying to write out the full instructions of how to make these changes I will demonstrate each of the techniques used in the rest of this post in an embedded video. This has the benefit of being able to see the exact steps that I need to do in Fork to achieve the intended goal and avoids any chance that I missed a step in my description.

The next thing that I'm going to demonstrate is using the "fixup" command when in an interactive rebase. This is another useful tool when trying to not show the reviewer any of your failed experiments. The way I like to think of this particular technique is that, firstly, all the commits in your PR should be considered as being additive in that they are adding a feature or a concept to the codebase (even if you're actually deleting files). Each of the commits should be building on top of each other to get from the current state of the repo to the added concept, and you should do that in a straight line and not zig-zag back on yourself. What this means in practice is that you should never see a commit that "fixes lint" on something that was added in a previous commit. So let's fixup some of these "fix lint". Commits now.

Looking through some of the other commits I can see there is one that fixes some lint issues that were actually introduced in multiple different commits. This makes it a tiny bit more difficult to fixup because we can't just apply it to a single commit in our existing history. The way around this is to split this single commit into multiple commits using the "edit" command during an interactive rebase:

Once the commit has been split we can then use fixup again exactly as we did in the previous example.

Now that we have the skills needed to cleanup all the "fix" commits, I'm going to go ahead and apply these techniques to the rest of the branch. Just to be clear, I'm not going to use any techniques other than what I have explained so far in this post.

After about 20 minutes of investigating and rebasing I have ended up with a new history that is a significant improvement from what we had before

This has improved the commit list from 34 commits to 22! But this is still far too many commits for a single reviewer to be expected to look at all at once. The problem that we currently face is that there are multiple "features" or "logical changes" happening in this branch, and if we were to convert this branch into a PR then we would be breaking one of my only rules: a PR should only be making a single logical change.

So let's start pulling out some logical Pull requests! I'll start with a super simple one to demonstrate using interactive rebase or cherry-pick to pull out a single commit.

As you can see in the video, creating the new branch using interactive rebase or using cherrypicking results in identical branches. It doesn't matter which method that you use but I would recommend getting comfortable with each method as they both can be useful depending on the situation. Once you have this branch you can go through your normal process of pushing to GitHub and opening a PR. Once that PR is merged we will then need to rebase our feature branch on master, which should usually automatically remove the commits that we split out into the other PR. This time it just needs to be a standard rebase without using interactive rebase, and it should cause no issues. I have included a quick video of that process for completeness:

And that's it! I have now shown you all of the techniques that you need to be able to clean up your git history and truly make your reviewer's days better. I would encourage you to try out these techniques and get more comfortable with them over time, and hopefully you will start reaching for these techniques on a regular basis.

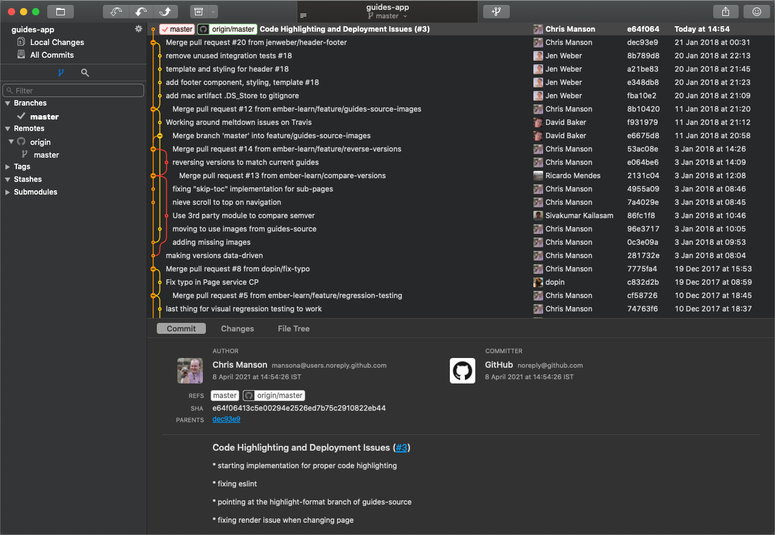

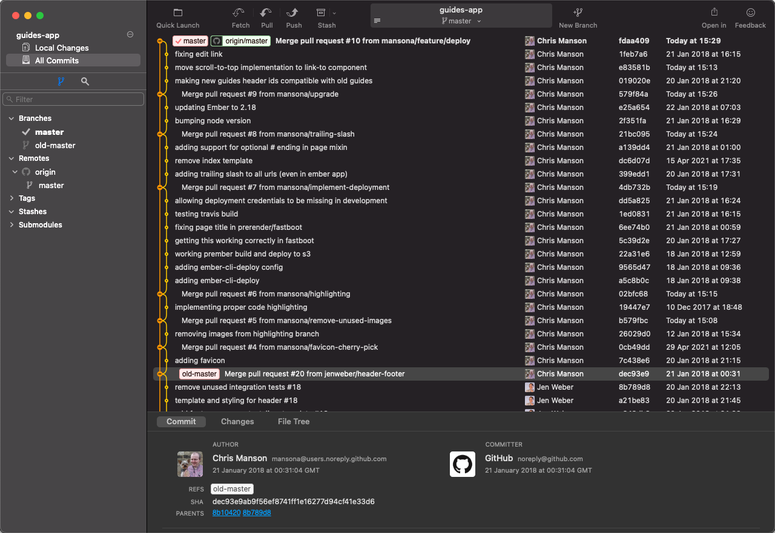

I've spent a little bit of time applying the techniques described above to the rest of the commits in the feature/deploy branch as a demonstration of what it will ultimately look like. Here it is for reference:

This screenshot is a perfect example of a git history in my opinion. It has plenty of very small PRs that only have one commit in them, allowing the PR to be reviewed and merged very quickly. It also has clear and understandable commits in the larger PRs that can be reviewed commit-by-commit if the reviewer would prefer, while still encapsulating the similar commits in a branch (and not over-splitting branches and PRs).

anchorSummary

When I started writing this post I didn't expect it to be quite as long as it turned out, but hopefully this can be a holistic guide for anyone who is using Git but doesn't have a clear mental model for best practices around PRs, merging, squashing, and rebasing.

While everything in this post is completely optional, I hope that you can see the benefits and maybe adopt some of the ideas in your own workflow.