anchorPlanning on the Macro Level

When it comes to planning software projects on the macro level, there's two extremes – trying to plan everything up-front or accepting the impossibility of getting that right and not bothering to plan anything at all. While most teams will find themselves somewhere in the middle between those two, it's still worth reviewing them in a bit more detail.

anchorOver-planning

Historically, in a waterfall based world, over-planning was widely used. The idea behind this approach is to plan out the entirety of the project up-front in excessive detail, project that plan on to a timeline and then execute it. Teams practicing over-planning would write long and detailed specifications that describe all aspects of the project. They would then break that specification down into a backlog of smaller tasks, estimate that backlog somehow and extrapolate how long the project will take; eventually leading to statements like "We can build the social network for elephants as described in the 587 page long specification in 67 weeks and it will cost a total of 1.34 Mio. €".

As we all know now this almost never works as planned, deadlines are missed and budgets overrun – as countless examples show.

anchorUnder-planning

The opposite of that approach is doing only very little or no up-front planning at all and just running off. While that removes a lot of pressure from development teams (designers and engineers in particular), other stakeholders that have legitimate needs with regards to predictability and insight into a project's progress are left in the cold. The marketing team will not know when to book the billboards in the local zoo and the product experts can't set up the user testing session with a group of sample elephants as they don't know what features they will be able to test when or whether there will be a coherent set of functionality that even makes sense as a unit at any time at all.

anchorFailing agilely

No teams (that I have seen at least 🤞) in reality strictly practice either of these two extremes. The classic waterfall model fortunately is a thing of the past now and the shortcomings of having a team just run off with no plan are too obvious for anyone to be brave (or naive) enough to try it. In fact, developing products iteratively following an "agile" process (whatever precisely that term might mean for any particular team) is a widely accepted technique now. That way, the scope and thus complexity and risk is significantly reduced per iteration (often referred to as "sprints" – which I think is a horrible term but that's a blog post of its own right) into something much more manageable. All planning is then based on estimates of relatively small tasks (using e.g. story points) and productivity measures based on those estimates (the team's "velocity").

In reality however, adopting an agile, iterative process (whether that's Scrum, a team's own interpretation of it or something completely different) will not magically solve all of the above problems. Teams will still face budget overruns and not be able to give reliable estimates even given the short time horizon of a two week iteration. Unforeseen and unplanned-for complexities and challenges will still be uncovered only after a task was started, many tasks will span multiple sprints unexpectedly and already completed features will regularly have to be revisited and changed even before launching an MVP.

Having moved planning from the macro level where it did reside with the classic waterfall approach to the micro level of an iteration, that level is also where the problems were moved to.

anchorPlanning on the Micro Level

Planning on the micro level of an iteration means scoping, bundling and estimating concrete, actionable units of work. There are countless names for these units which depend on the particular process or tool in use but in reality it doesn't matter whether you call them issues, (user) stories or TODOs, whether you organize them in trees with several levels of subtasks and/or overarching epics – what they are is tasks that one or several team members can work on and complete, ideally in relatively short time (like a few days at most). A bundle of tasks defines the scope of an iteration which is what we're planning for on the micro level.

anchorIsn't a plan just a guess anyway?

There's a very popular quote from the team behind Basecamp, a bootstrapped company that built a hugely successful project management SaaS with the same name:

Basecamp explain the idea in more detail in their bestselling book "Rework". The quote is both great and widely misunderstood. What it means is that anything beyond a pretty small scope is inherently not plannable and any plan anyone makes up for it, is essentially nothing more than a guess. As explained above that is very much true at the macro level where scope and complexity are way too big for anyone to be able to fully grasp. What the quote does not mean however, is that you can never prepare and pre–assess any work when the scope is limited – which is the fact on the micro level of an iteration.

Yet, many project teams use "planning is guessing" as an excuse to refuse doing any thorough up-front analysis or preparation of tasks at all. Even if teams spend time on preparing work before starting it, that preparation is often superficial only, leaving a lot of uncertainty and risk to be uncovered only after work on a task has started. Understanding any task fully and in its entirety does of course require actively working on and in fact completing the task. It is however very well possible to analyze tasks to uncover hidden complexity, dependencies and implications – not only from an engineering perspective but also from the perspectives of other stakeholders like design, product, marketing etc.

Thorough analysis and preparation of tasks will help in understanding the scope of the tasks, identifying dependent work that needs to be done before or in consequence or weighing alternative implementation options against each other as well as against other priorities. All that reduces the uncertainty that is associated with a task and even while you won't be able to fully eliminate all uncertainty, eliminating a big part or maybe most of it significantly improves the reliability of estimates and minimizes unplanned work that is usually necessary when running into unforeseen complications only after work has started.

anchorWinning at Planning through Preparation

In order to improve planning on the micro level, it is essential to conduct thorough preparation. I will present four key techniques that are essential for effective preparation of tasks and that Mainmatter has been practicing successfully for years.

anchor1. The source of tasks

First, let's look at where the work that a product team conducts typically originates from. In most cases, there are more or less only two sources – feature stories that are defined by the product team and technical changes like refactorings driven by the engineering team. Ideally both kinds of work are equally represented as tasks although in many cases that is not the case for purely technical work. Since that work happens anyway though, not representing it as individual tasks is a big mistake and leads to part of the work that is happening not being visible to all stakeholders with all of the negative consequences that come with that.

So let's assume all work that is happening in a project is equally represented as tasks. Still, in many cases stakeholders would only define their own tasks without receiving much input from each other. Each stakeholder then pushes for their tasks to be planned for in a particular iteration. That is not an effective way of collaborating though and generally not in the best interest of the success of the project. A successful project needs to take all of the stakeholder's individual perspectives and priorities into account. After all, neither focusing on features only and giving up technical aspects like long-term maintainability and extensibility of the product, nor refactoring the code to perfection but only shipping too little too late, will result in a success for the business.

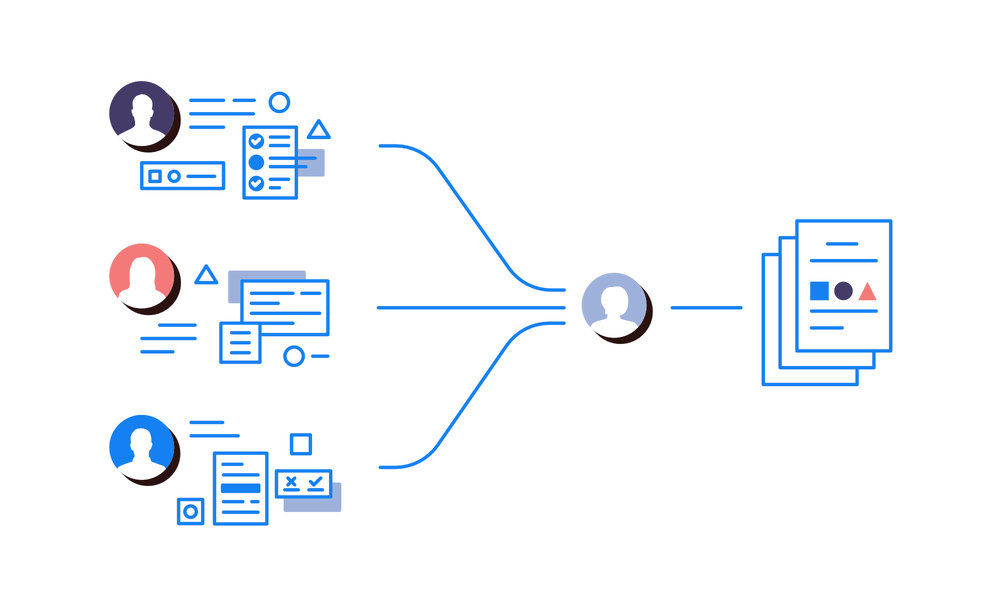

anchorCommunication 💬 and Collaboration 🤝

Successful teams communicate openly and directly and collaborate closely. While this might read like an obvious statement, in reality there is often lots of room for improvement. Many teams build walls between stakeholders when they really would all have to collaborate – from product experts to engineering and design but also marketing, finance and potentially others. That collaboration starts with agreeing what work should be done in which order and to what level of depth. Having a collaborative process for this in place makes the entire development process more effective by eliminating unnecessary complexity or preventing longer-term decline of a team's velocity.

In many cases for example, there will be different ways to implement a particular feature that the product experts want to add with drastically different levels of associated development complexity. Often, it might not matter much from a product perspective which of these alternatives is chosen and finding that out early can save the designers and engineers a substantial amount of time and effort. In other cases, the engineering team might see the necessity for particular refactorings but there might be conflicting commitments that the marketing team has to fulfill which justify delaying the refactoring to a later iteration. In other cases yet, a refactoring might have substantial positive consequences for the product also from a user's perspective which would lead to wide support of the undertaking from all stakeholders. Uncovering all these situations is only possible by communicating and collaborating, not only when conducting work but already when scoping and planning it. Yet again, as obvious as this might seem, many teams struggle hard with the consequences of not being as open.

anchorRotating Responsibility

In our projects, we leverage an iteration lead role. The iteration lead is responsible for identifying, scoping and preparing all work that is planned to happen in a particular iteration. They will collect input from all stakeholders, prepare proper tasks for each request (more on what a proper task is below), prioritize tasks and present the result to the product team before kicking off an iteration. Of course, the iteration lead cannot have all of the detailed knowledge that each stakeholder has about their field and they are not supposed to – they will reach out to the respective experts, bring people together and make sure communication happens.

The iteration lead role is not fixed to a particular member of the product team but set up as a rotating role among the entire team instead – every other iteration the role moves on to a new team member so that every product or marketing expert, designer or engineer will assume it periodically. Rotating the role among the entire team is a great way to ensure people get to understand and appreciate each stakeholder's perspective and are not stuck with their own point of view only. That appreciation is not only beneficial for the team spirit but also significantly improves collaboration in our experience. We do not even work with project managers at all and depend on the iteration lead role instead. In fact, we see the project manager role – at least in its classic shape as someone directing the product team – as an organizational anti-pattern that is most often necessary only as a consequence of teams that are really dysfunctional at their core.

anchor2. Focussing on the present

As described above, many teams will prepare and maintain an extensive backlog filled with all tasks that anyone ever brought up or that are expected to eventually be required for a particular project. What seems like a good idea in order to have a more complete understanding of the entirety of a project, in an iterative process the only work that ever matters is what the team is currently doing and what is being prepared and planned for the next iteration. Everything else can safely be ignored as it is completely unknown in which way a particular task will be addressed in the future or whether it will be at all. Everyone has seen projects with huge backlogs that seem to imply lots and lots of work that still needs to be done while everyone knows that 90% of the tasks will likely never be taken on and 75% of them are already outdated anyway (these are made-up numbers only backed by my personal experience ✌️).

Actively keeping a backlog is most often simply a waste of time. That is not only the case for feature tasks but also for bug reports – a bug that has not been addressed for the past six months is unlikely to be addressed in the coming six months. At the same time it also is unlikely to be really relevant to anyone and thus unlikely to ever be solved at all (unless it is solved automatically as a consequence of a change to the underlying functionality maybe).

anchor3. Scoping and analysis

Once work has been sourced from the project stakeholders, it needs to be well understood and scoped. This is a critical step in order to fully understand the tasks in their entirety and prevent the team from running into unforeseen problems once the work has started. Of course, it is not possible to always prevent all problems that might occur at a later point altogether but the more that is uncovered and addressed earlier rather than later, the smoother completing each task will go.

First, all of a task's preconditions must be met before it can be worked on at all. That can include designs being ready or user tests having been conducted and analysed. It might also mean contracts with external providers have been signed or marketing campaigns have been booked. Just as important as the preconditions are a task's consequences which can be technical ones but also related to features or design – a technical change might require a change to the deployment and monitoring systems; changing feature A might also require adapting feature B in an unrelated part of the application so that both features make sense together; switching to a new design for forms might have consequences for the application's accessibility and marketing materials outside of the application. Most of such consequences can usually be identified and planned for up-front – in many cases even with relatively little effort.

Lastly, fully understanding a task should result in the ability to break it down into a series of steps that need to be performed in order to complete it. These steps do not need to be extremely fine-grained ("change line x in file y to z") or be limited to what the engineering team needs to do. Instead, they should reflect on a high level all changes that need to be made to all aspects of the application and related systems to complete the task. Sometimes it turns out that for a particular task it is not possible yet to identify and clearly describe these steps. In these cases, it is recommendable to conduct a spike and prepare a prototype for the aspect that is yet unclear first in order to understand it better. While this technique comes from the engineering world, it is not limited to it and is just as valuable for designers and product experts as well (e.g. for validating particular feature flows or design approaches with real users before implementing it).

Some teams are adopting full-on RFC processes for scoping and defining work like this. In an RFC process, someone or a group of people would write a document explaining an intended change in relative detail, then ask all affected stakeholders (or anyone really) for feedback until consensus is reached and the RFC is ready to be implemented. While that can come with formalities and process overhead that might not always be justified, it is generally a good approach and ensures the above points are addressed. Generally, an RFC process is likely the better suited the wider the topic of a task is and the larger the team size is. For smaller teams, it might be sufficient to collaboratively edit a task in the respective tool directly.

anchor4. Writing it all down

The final step for proper preparation of tasks is to write all of the information acquired in the previous steps down in the tool of choice. As stated above, it does not matter what tool that is – good tasks share some common characteristics that are independent of any particular tool:

- They describe what is to be done and why, potentially accompanied by screenshots, mockups/sketches or other visuals that help understand the desired outcome; it is also beneficial to add a summary of the task's history, covering previous related changes or alternative approaches that have been ruled out in the process of scoping the task and also providing the reasons for those decisions.

- They include reproduction steps if the task describes a bug; ideally those are visualized with a screen recording or other media.

- They list concrete steps that must be taken in order to complete the task (see "3. Scoping and analysis" above).

- They include all necessary materials that are needed for the task; this could be visual assets, links to online documentation for third party libraries or APIs or contact details for external parties involved in an issue etc.

- They reference any open questions that need to be answered, or risks that have been identified but could not be resolved up-front and that might prevent the task from being completed.

- They are a discrete unit of work; tasks should only contain related requirements and ideally not represent more than a few days of work - larger tasks can often be broken down into multiple smaller ones, possibly even allowing for work to happen simultaneously.

A well prepared task would enable any member of the product team that is an expert in the respective field to take on and complete the task. However, tasks are not only written for the team member that will work on them but also for any other stakeholder that has an interest in the project and needs to know what is going on at any time – be it at the time the task is actively planned or being worked on or later when trying to understand why something was done retroactively, what the intentions and considerations were at the time etc.

anchorConclusion

Teams are not successful because they adopt a particular process (and potentially even get themselves certified) or adopt the latest and greatest project management tools. Success is mostly enabled through relatively simple values:

- open and direct communication as well as close collaboration among all stakeholders

- identifying and resolving as much uncertainty and uncovering as much hidden complexity as possible on the task level before work on the task starts

- ignoring all work that is not known to be relevant at the time an iteration is planned and executed

- being detailed (potentially overly detailed) when describing tasks

Doing all this thoroughly requires a bit of extra time (the iteration lead would easily be occupied a few days per week with that in addition to the time the respective experts for each topic invest to give their input). However, thanks to much improved effectiveness as well as the benefits of improved certainty and planability, that time pays off manyfold.

We have written all of the values and techniques introduced in this post in much more detail in our playbook and welcome everyone to adapt these patterns and share their experience and feedback with us.